An Historical Overview of African-American Exclusion in Arizona

Like most states in the 20th century, Arizona had roots of racism and segregation existed.

Laws were put into place to prevent blacks and whites from attending the same schools, and they forced segregation in housing and neighborhoods in the predominantly white desert state.

As laws changed and diversity increased over time, legally sanctioned segregation disappeared, but seclusion between whites and blacks remains in Arizona.

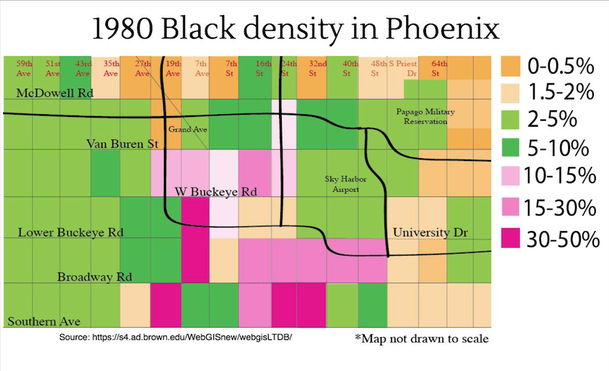

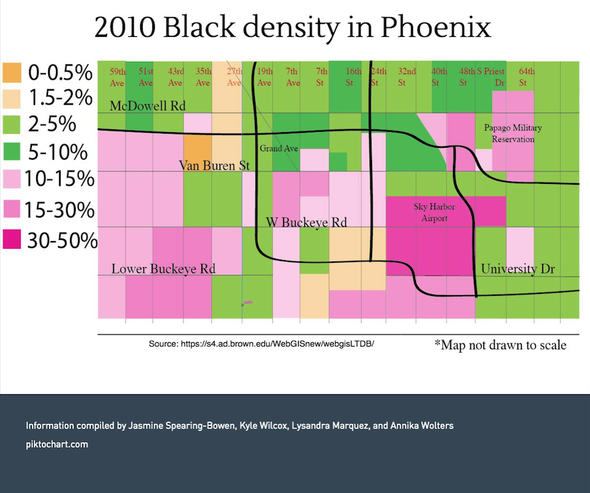

In the 1960’s, south Phoenix housed a majority of the blacks in the city and even in 2010, that remained the same.

Arizona clearly has a divide in the community that has not wavered with the test of time.

THEN

During the mid-1900s, areas of cities like Phoenix were redlined, and African-Americans faced oppression especially with housing.

Fred Holloway, an African-American resident of Phoenix for more than 50 years, discussed his time finding a place to live only 12 years after the Thanksgiving Day Riot stained Phoenix.

“I was looking for houses and naturally, you look in the community that’s available to you," said the 86-year-old. “I didn’t look outside of that community, so I looked behind the capitol, which at the time was one of the best places in town to live.”

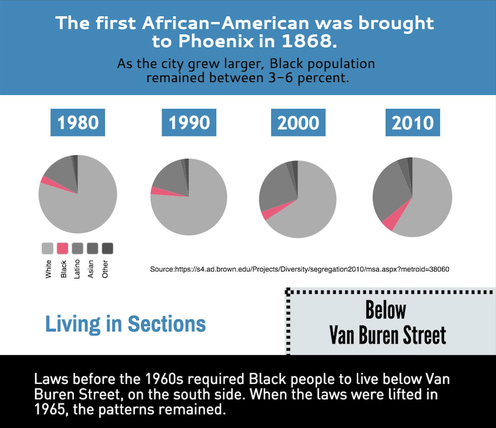

Holloway recalled that Van Buren Street was known as the segregated threshold line in Phoenix and many blacks did not live north of it.

Fred Holloway, an African-American resident of Phoenix for more than 50 years, discussed his time finding a place to live only 12 years after the Thanksgiving Day Riot stained Phoenix.

“I was looking for houses and naturally, you look in the community that’s available to you," said the 86-year-old. “I didn’t look outside of that community, so I looked behind the capitol, which at the time was one of the best places in town to live.”

Holloway recalled that Van Buren Street was known as the segregated threshold line in Phoenix and many blacks did not live north of it.

“The first black person that I knew that lived north of Van Buren was Ragsdale,” said Holloway. “He used to own the funeral home.”

This was an extreme issue during those times as people of color faced resistance when trying to live in white neighborhoods.

An academic scholar at Arizona State University (ASU) School of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies detailed the discriminatory housing laws.

“In Phoenix and in Arizona like the rest of the United States, there were what they call restrictive housing covenants, where they could write into the mortgages who you could and could not sell your house to,” said Matthew Delmont, a 38-year-old Tempe resident. “So this would say ‘you could not sell this home to African-Americans, to Latinos, to Jewish people.’ That was one of the main factors that kept neighborhoods segregated.”

In addition, it was hard for blacks to even secure a loan for a home.

Delmont said African-Americans in Phoenix faced extreme difficulty when trying to apply for home loans to acquire houses, which resulted in housing segregation in the 1940s and 1950s.

In 1968, the Fair Housing Act was enacted nationally to prevent discrimination against people of color when buying and selling homes. Segregation survived though, as blacks were still excluded from many neighborhoods.

Lenders were able to keep the communities limited by manipulating home buyers.

This was an extreme issue during those times as people of color faced resistance when trying to live in white neighborhoods.

An academic scholar at Arizona State University (ASU) School of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies detailed the discriminatory housing laws.

“In Phoenix and in Arizona like the rest of the United States, there were what they call restrictive housing covenants, where they could write into the mortgages who you could and could not sell your house to,” said Matthew Delmont, a 38-year-old Tempe resident. “So this would say ‘you could not sell this home to African-Americans, to Latinos, to Jewish people.’ That was one of the main factors that kept neighborhoods segregated.”

In addition, it was hard for blacks to even secure a loan for a home.

Delmont said African-Americans in Phoenix faced extreme difficulty when trying to apply for home loans to acquire houses, which resulted in housing segregation in the 1940s and 1950s.

In 1968, the Fair Housing Act was enacted nationally to prevent discrimination against people of color when buying and selling homes. Segregation survived though, as blacks were still excluded from many neighborhoods.

Lenders were able to keep the communities limited by manipulating home buyers.

Delmont said that mortgage lenders would “steer” African-Americans to predominantly black neighborhoods and do the same to whites. There were no laws preventing them from encouraging the residents to move to a certain area.

Another major barrier for African-Americans in Arizona was education.

Schools were segregated in cities like Phoenix as blacks were forced to go to certain schools in their predominantly African-American neighborhoods. Many of them attended schools in south Phoenix.

Another major barrier for African-Americans in Arizona was education.

Schools were segregated in cities like Phoenix as blacks were forced to go to certain schools in their predominantly African-American neighborhoods. Many of them attended schools in south Phoenix.

According to statistics gathered by the Athenaeum Public History Group, 20,919 African-Americans lived in Phoenix in 1960 and 95 percent of them lived south of Van Buren Street.

Because of the huge population of blacks living in that area, many attended schools close by. Even after segregation was outlawed, the schools in those areas remained predominantly black.

In an effort to enforce desegregation, busing was court ordered as a way to integrate schools more. Children would be driven from their home neighborhoods to other neighborhoods in school buses in order to increase the diversity.

Delmont discussed how busing caused backlash from the white community and created a burden for black students as they were forced to travel far to schools they were not welcome at.

He said ultimately, busing failed.

Because of the huge population of blacks living in that area, many attended schools close by. Even after segregation was outlawed, the schools in those areas remained predominantly black.

In an effort to enforce desegregation, busing was court ordered as a way to integrate schools more. Children would be driven from their home neighborhoods to other neighborhoods in school buses in order to increase the diversity.

Delmont discussed how busing caused backlash from the white community and created a burden for black students as they were forced to travel far to schools they were not welcome at.

He said ultimately, busing failed.

NOW

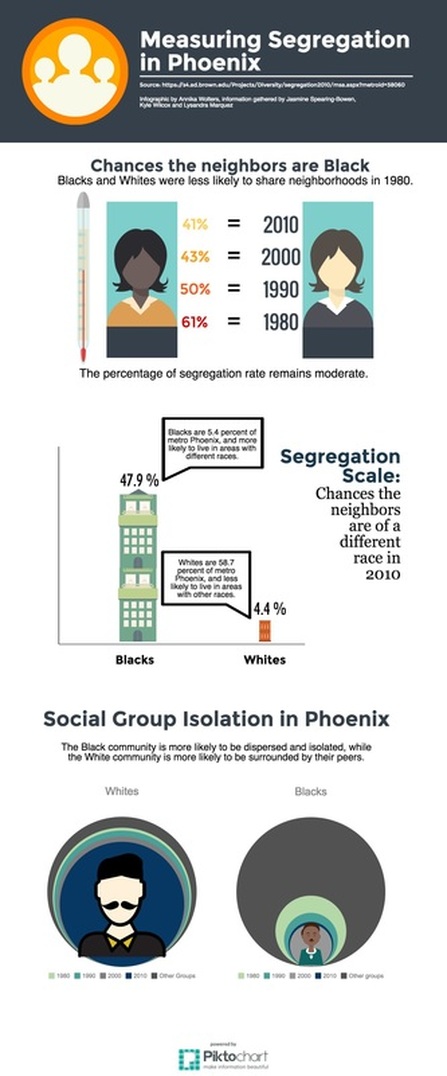

Fast forward to the 21st century, the population of Arizona is still predominantly white, and isolation of races still exists among neighborhoods and schools.

According to statistics gathered by Brown University, Maricopa and Pinal County had a combined population in 2010 of 4.2 million, which was made up of 58.7 percent whites and 5.4 percent blacks.

The large disparity between the two races has led to many neighborhoods, especially in southern Phoenix, being composed of mainly blacks.

According to statistics gathered by Brown University, Maricopa and Pinal County had a combined population in 2010 of 4.2 million, which was made up of 58.7 percent whites and 5.4 percent blacks.

The large disparity between the two races has led to many neighborhoods, especially in southern Phoenix, being composed of mainly blacks.

Dr. Matthew Whitaker, founder of the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy and winner of the 2014 Arizona Diversity Leadership Alliance Inclusive Workplace Award at ASU explained the remaining presence of segregation in Arizona.

“Segregation is as big a problem, if not a bigger problem than it was back then,” said Whitaker. “If you look at statistics right now it shows you that people of color are more hyper-segregated than they were in 1968, meaning that most people of color will be born and will die in communities that are dominated by people who look like them.”

An ASU associate professor at the College of Public Service and Community Solutions, who has researched housing and neighborhood policies in Arizona for several years, shared a similar outlook.

“Even though Phoenix is not as segregated as some of the cities back East and the Midwest in terms of race, it still is very segregated in terms of schools and neighborhoods in that we have a concentration of African-Americans in south Phoenix still and city central south neighborhoods,” said Joanna Lucio.

According to statistics gathered by Brown University, a map comparison of Phoenix showed that areas south of Van Buren Street were 10-50 percent more concentrated with blacks in 2010 than 1980. The statistics show that the southern area has remained heavily populated by blacks.

“Segregation is as big a problem, if not a bigger problem than it was back then,” said Whitaker. “If you look at statistics right now it shows you that people of color are more hyper-segregated than they were in 1968, meaning that most people of color will be born and will die in communities that are dominated by people who look like them.”

An ASU associate professor at the College of Public Service and Community Solutions, who has researched housing and neighborhood policies in Arizona for several years, shared a similar outlook.

“Even though Phoenix is not as segregated as some of the cities back East and the Midwest in terms of race, it still is very segregated in terms of schools and neighborhoods in that we have a concentration of African-Americans in south Phoenix still and city central south neighborhoods,” said Joanna Lucio.

According to statistics gathered by Brown University, a map comparison of Phoenix showed that areas south of Van Buren Street were 10-50 percent more concentrated with blacks in 2010 than 1980. The statistics show that the southern area has remained heavily populated by blacks.

Delmont said the lack of blacks and whites attending schools together is a result of past political choices and a widespread disinterest of the common citizen wanting the best education for the community as a whole.

Delmont also took a different approach to the current housing divide.

“The way our courts have decided recently, the kind of segregation that we have right now would be termed legal because it’s following socioeconomic patterns,” said Delmont.

He explained the government sees it more as groups of low income people that in are the same areas, which happens to be blacks.

Although, one person believes housing in Arizona has been going in the right direction.

William Emerson, the Deputy Housing Director in Phoenix, explained his optimism of Phoenix’s current diversity in neighborhoods.

Delmont also took a different approach to the current housing divide.

“The way our courts have decided recently, the kind of segregation that we have right now would be termed legal because it’s following socioeconomic patterns,” said Delmont.

He explained the government sees it more as groups of low income people that in are the same areas, which happens to be blacks.

Although, one person believes housing in Arizona has been going in the right direction.

William Emerson, the Deputy Housing Director in Phoenix, explained his optimism of Phoenix’s current diversity in neighborhoods.

I think in the last seven years we've seen a generational change in the way we approach race. We value it."

-William Emerson

“I think we’re on the right track,” said the Phoenix resident. “I think in the last seven years we’ve seen a generational change in the way we approach race. We value it.”

Emerson added that more neighborhoods feature a mix of income and race and that his office is committed to diversifying developments in every community.

Like Emerson, many want to see change in Arizona because a division in the community does not benefit anyone and diversity is good.

“When you have a lack of racial diversity, a lack of economic opportunity, you have a smaller world, and it’s true whether that’s all whites, all black, all Latino or anything like that,” said Emerson.

Emerson added that more neighborhoods feature a mix of income and race and that his office is committed to diversifying developments in every community.

Like Emerson, many want to see change in Arizona because a division in the community does not benefit anyone and diversity is good.

“When you have a lack of racial diversity, a lack of economic opportunity, you have a smaller world, and it’s true whether that’s all whites, all black, all Latino or anything like that,” said Emerson.